EGU Assembly 2013

Presentation by Dr Peter Carter

Presentation by Dr Peter Carter

Vienna AGU "Sustainability transitions of the socio-ecologic system"

Topic Global change processes cause a large challenge for society. Significant changes in some of our current ways of living are necessary in order to not transgress important natural boundaries. For example, CO2 emissions need to be drastically reduced to avoid severe effects from climate change. These changes in society are likely to cause an overall transition of the socio-ecological system.

Is the World in a State of Climate Change Planetary Emergency?

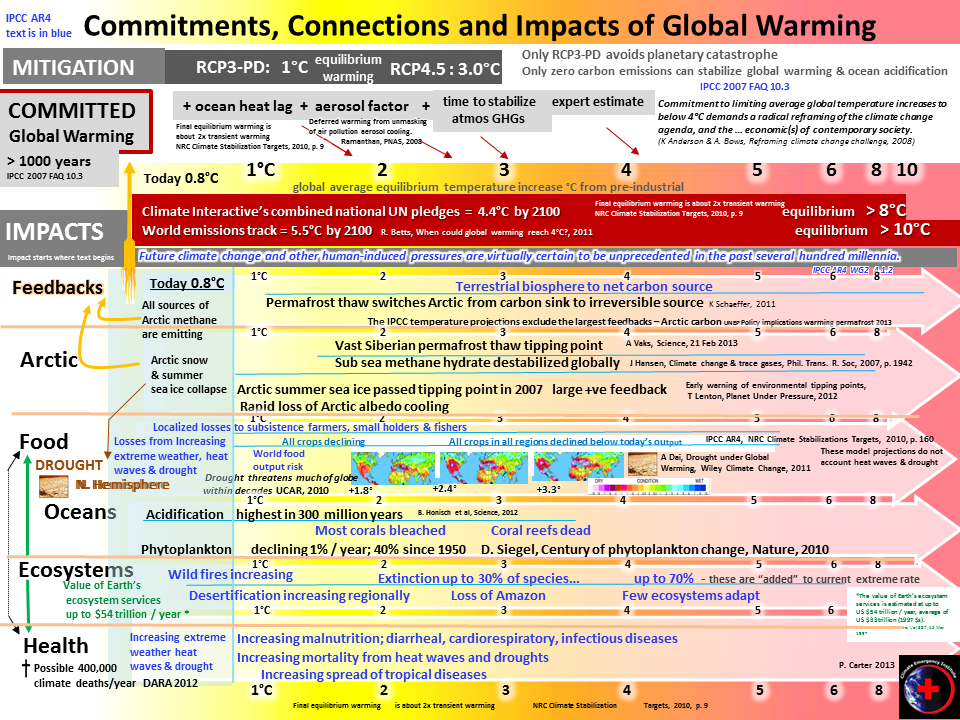

Leading climate change experts have made public statements that the world is beyond dangerous interference with the climate system, committed to a warming of 3-5ºC, facing a risk of global climate catastrophe, and in a state of planetary emergency, but these conclusions are not informing climate change policy. The evidence for these statements is examined and presented in this paper. The main parameters considered are world food security and carbon feedback "runaway" or rapid global warming. 2012 was a record year for Arctic albedo loss, which amplifies Arctic warming and drives Arctic methane feedback emissions. Since 2007, atmospheric methane is experiencing a renewed, sustained increase due to feedback emissions. All potentially large positive Arctic feedbacks are operant. These include albedo loss from disappearing snow and summer sea ice; methane released from peatlands, thawing permafrost and sea floor methane hydrates; and nitrous oxide from cryoperturbed permafrost. Increasing extreme weather events have caused regional crop productivity losses on many continents since 2000. The loss of Arctic albedo might be driving extreme heat and drought in the northern hemisphere. Today the formal national pledges for emissions reductions filed with the UN, combined, commit humanity to a warming of 4.4ºC (Climate Interactive) by 2100, which is more than 8ºC eventually after 2100, and there are no initiatives to change this. The International Energy Agency warns that the current global economy is on track for a warming of 6ºC by 2100. A simple yet novel summation approach of all unavoidable sources of warming estimates the committed unavoidable warming to be 3ºC by 2100. What are the implications of these future commitments for world food security and the risk of runaway climate change? The paper considers how these commitments and the policy-relevant research findings can inform policy making with respect to an appropriate science-based mitigation response.

Proposition:

The evidence from observed extreme impacts, trends and projections affecting all regions is now so overwhelming that it is clear we all live in state of committed global climate disruption emergency.

The Arctic is undergoing extremely rapid (if not abrupt) change.

It is now warming three times faster than the rest of the planet.

The Arctic summer sea ice passed its ice- free summer tipping point in 2007 and is now under a heading to start being summer sea ice free, in as soon as a few years.

The loss of Arctic summer sea ice albedo cooling, and also the loss of far North snow albedo, is a very large positive climate system feedback with catastrophic implications.

This has already triggered the Arctic to emit all three greenhouse gases, mainly methane but also carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, from all (previously safe) sources of Arctic methane.

Because there are no negative feedbacks to stop this multiple cascading positive feedback process, without an emergency intervention this will lead to a progressive increase in the heating of the Arctic and the Northern Hemisphere and will further accelerate global warming. This makes standard ideas about mitigation or adaption inadequate.

The loss of Arctic albedo cooling is bound to adversely affect the world's prime agricultural regions in the normally temperate Northern Hemisphere.

There is an increase in extreme heat and drought affecting the Northern Hemisphere and therefore it is possible that this effect is already happening.

The stabilization of the Arctic summer sea ice and Northern Hemisphere snow cover, with the stabilization of Arctic carbon and the temperate Northern hemisphere climate, is our most urgent imperative.

Topic Global change processes cause a large challenge for society. Significant changes in some of our current ways of living are necessary in order to not transgress important natural boundaries. For example, CO2 emissions need to be drastically reduced to avoid severe effects from climate change. These changes in society are likely to cause an overall transition of the socio-ecological system.

Is the World in a State of Climate Change Planetary Emergency?

Leading climate change experts have made public statements that the world is beyond dangerous interference with the climate system, committed to a warming of 3-5ºC, facing a risk of global climate catastrophe, and in a state of planetary emergency, but these conclusions are not informing climate change policy. The evidence for these statements is examined and presented in this paper. The main parameters considered are world food security and carbon feedback "runaway" or rapid global warming. 2012 was a record year for Arctic albedo loss, which amplifies Arctic warming and drives Arctic methane feedback emissions. Since 2007, atmospheric methane is experiencing a renewed, sustained increase due to feedback emissions. All potentially large positive Arctic feedbacks are operant. These include albedo loss from disappearing snow and summer sea ice; methane released from peatlands, thawing permafrost and sea floor methane hydrates; and nitrous oxide from cryoperturbed permafrost. Increasing extreme weather events have caused regional crop productivity losses on many continents since 2000. The loss of Arctic albedo might be driving extreme heat and drought in the northern hemisphere. Today the formal national pledges for emissions reductions filed with the UN, combined, commit humanity to a warming of 4.4ºC (Climate Interactive) by 2100, which is more than 8ºC eventually after 2100, and there are no initiatives to change this. The International Energy Agency warns that the current global economy is on track for a warming of 6ºC by 2100. A simple yet novel summation approach of all unavoidable sources of warming estimates the committed unavoidable warming to be 3ºC by 2100. What are the implications of these future commitments for world food security and the risk of runaway climate change? The paper considers how these commitments and the policy-relevant research findings can inform policy making with respect to an appropriate science-based mitigation response.

Proposition:

The evidence from observed extreme impacts, trends and projections affecting all regions is now so overwhelming that it is clear we all live in state of committed global climate disruption emergency.

The Arctic is undergoing extremely rapid (if not abrupt) change.

It is now warming three times faster than the rest of the planet.

The Arctic summer sea ice passed its ice- free summer tipping point in 2007 and is now under a heading to start being summer sea ice free, in as soon as a few years.

The loss of Arctic summer sea ice albedo cooling, and also the loss of far North snow albedo, is a very large positive climate system feedback with catastrophic implications.

This has already triggered the Arctic to emit all three greenhouse gases, mainly methane but also carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide, from all (previously safe) sources of Arctic methane.

Because there are no negative feedbacks to stop this multiple cascading positive feedback process, without an emergency intervention this will lead to a progressive increase in the heating of the Arctic and the Northern Hemisphere and will further accelerate global warming. This makes standard ideas about mitigation or adaption inadequate.

The loss of Arctic albedo cooling is bound to adversely affect the world's prime agricultural regions in the normally temperate Northern Hemisphere.

There is an increase in extreme heat and drought affecting the Northern Hemisphere and therefore it is possible that this effect is already happening.

The stabilization of the Arctic summer sea ice and Northern Hemisphere snow cover, with the stabilization of Arctic carbon and the temperate Northern hemisphere climate, is our most urgent imperative.

CLIMATE EMERGENCY INSTITUTE

The health and human rights approach to climate change

The health and human rights approach to climate change

EGU Assembly 2017

Dr. Peter Carter

Dr. Peter Carter

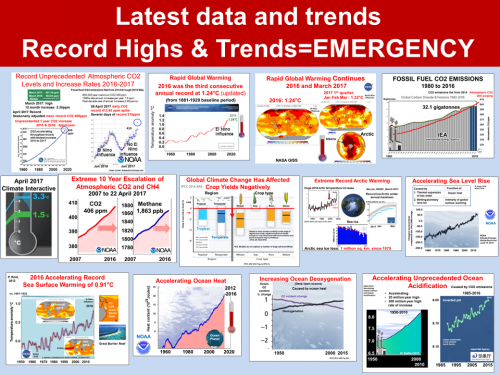

Big emergency picture image of data to April 2017

.

.

EGU 2017 Abstract (updated April 2017)

Title of paper

From up to date climate and ocean evidence with updated UN emissions projections, the time is now to recommend an immediate massive effort on CO2.

Author Dr. Peter Carter

Affiliation Climate Emergency Institute

This paper provides further compelling evidence for ‘an immediate, massive effort to control CO2 emissions, stopped by mid-century’ (Cai, Lenton & Lontzek, 2016).

Atmospheric CO2 which is now 406 ppm (seasonally adjusted mean) still accelerating, on the worst case IPCC AR5 scenario, despite flat emissions since 2014 and now 2016 (IEA), with a 2015 and 2016 >3ppm unprecedented spike in Earth history (A. Glikson), is on the worst case IPCC scenario.

Atmospheric methane is increasing faster than its past 20-year rate, almost on the worst-case IPCC AR5 scenario (Global Carbon Project, 2016).

Observed direct effects of atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution are increasing faster tha ever.. This includes long-lived atmospheric GHG concentrations, radiative forcing, surface average warming, Greenland ice sheet melting, Arctic daily sea ice anomaly, ocean heat (and rate of going deeper), ocean acidification, and ocean de-oxygenation.

The atmospheric GHG concentration of 485 ppm CO2 eq (WMO, 2015) commits us to ‘about 2°C’ equilibrium (AR5). 2°C by 2100 would require ‘substantial emissions reductions over the next few decades’ (AR5).

Instead, the May 2016 UN update on ‘intended’ national emissions targets under the Paris Agreement projects global emissions will be 16% higher by 2030 and the November 2016 International Energy Agency update projects energy-related CO2 eq emissions will be 30% higher by 2030, leading to ‘around 2.7ºC by 2100 and above 3°C thereafter’. The April 2017 Climate Interactive projection of the INDCs is a warming of 3.3C by 2100, which is over 5.5C equilibrium warming after 2100.

Climate change feedback will be positive this century and multiple large vulnerable sources of amplifying feedback exist (AR5). ‘Extensive tree mortality and widespread forest die-back linked to drought and temperature stress have been documented on all vegetated continents’ (AR5). ‘Recent studies suggest a weakening of the land sink, further amplifying atmospheric growth of CO2’ (WMO, 2016). The Arctic has switched from a carbon sink to source (Nov 2016 NOAA Arctic Repoprt card)

Under all but the best-case IPCC AR5 scenario, surface temperature is projected to increase above 2ºC by 2100, which is above 3°C (equilibrium) after 2100, with ocean acidification still increasing at 2100. Ocean heat is increasing under all scenarios at 2100. For all producing regions ‘With or without adaptation, negative impacts on average crop yields become likely from the 2030s’ (AR5). Crop models do not capture all adverse effects. The climate change of 2030 is practically locked in. NASA NEX downscaled daily maximum temperature projections at 1.5°C are incompatible with today’s crop yields in major agricultural regions. Climate-change-related impacts from extreme events are high at 1.5ºC (AR5) and add to modeled crop declines. ‘Some unique and threatened systems are already at risk from climate change (high confidence)’ with ‘risk of severe consequences’ higher with warming of around 1.5ºC (AR5). At today’s surface temperature increase, ‘risks associated with tipping points become moderate’ and ‘increase disproportionately’ as temperature increases above 1.5°C (AR5). According to mitigation projections, global emissions would decline forthwith for a better than 66% chance of a 2ºC limit by 2100 (over 3°C after 2100). Failure to do so would risk the future sustainability of civilization and the human population. The IPCC does not make recommendations so this falls on scientists. By recommending immediate (emergency) massive action on CO2, the science community would make a momentous contribution to the future of humanity.

Title of paper

From up to date climate and ocean evidence with updated UN emissions projections, the time is now to recommend an immediate massive effort on CO2.

Author Dr. Peter Carter

Affiliation Climate Emergency Institute

This paper provides further compelling evidence for ‘an immediate, massive effort to control CO2 emissions, stopped by mid-century’ (Cai, Lenton & Lontzek, 2016).

Atmospheric CO2 which is now 406 ppm (seasonally adjusted mean) still accelerating, on the worst case IPCC AR5 scenario, despite flat emissions since 2014 and now 2016 (IEA), with a 2015 and 2016 >3ppm unprecedented spike in Earth history (A. Glikson), is on the worst case IPCC scenario.

Atmospheric methane is increasing faster than its past 20-year rate, almost on the worst-case IPCC AR5 scenario (Global Carbon Project, 2016).

Observed direct effects of atmospheric greenhouse gas (GHG) pollution are increasing faster tha ever.. This includes long-lived atmospheric GHG concentrations, radiative forcing, surface average warming, Greenland ice sheet melting, Arctic daily sea ice anomaly, ocean heat (and rate of going deeper), ocean acidification, and ocean de-oxygenation.

The atmospheric GHG concentration of 485 ppm CO2 eq (WMO, 2015) commits us to ‘about 2°C’ equilibrium (AR5). 2°C by 2100 would require ‘substantial emissions reductions over the next few decades’ (AR5).

Instead, the May 2016 UN update on ‘intended’ national emissions targets under the Paris Agreement projects global emissions will be 16% higher by 2030 and the November 2016 International Energy Agency update projects energy-related CO2 eq emissions will be 30% higher by 2030, leading to ‘around 2.7ºC by 2100 and above 3°C thereafter’. The April 2017 Climate Interactive projection of the INDCs is a warming of 3.3C by 2100, which is over 5.5C equilibrium warming after 2100.

Climate change feedback will be positive this century and multiple large vulnerable sources of amplifying feedback exist (AR5). ‘Extensive tree mortality and widespread forest die-back linked to drought and temperature stress have been documented on all vegetated continents’ (AR5). ‘Recent studies suggest a weakening of the land sink, further amplifying atmospheric growth of CO2’ (WMO, 2016). The Arctic has switched from a carbon sink to source (Nov 2016 NOAA Arctic Repoprt card)

Under all but the best-case IPCC AR5 scenario, surface temperature is projected to increase above 2ºC by 2100, which is above 3°C (equilibrium) after 2100, with ocean acidification still increasing at 2100. Ocean heat is increasing under all scenarios at 2100. For all producing regions ‘With or without adaptation, negative impacts on average crop yields become likely from the 2030s’ (AR5). Crop models do not capture all adverse effects. The climate change of 2030 is practically locked in. NASA NEX downscaled daily maximum temperature projections at 1.5°C are incompatible with today’s crop yields in major agricultural regions. Climate-change-related impacts from extreme events are high at 1.5ºC (AR5) and add to modeled crop declines. ‘Some unique and threatened systems are already at risk from climate change (high confidence)’ with ‘risk of severe consequences’ higher with warming of around 1.5ºC (AR5). At today’s surface temperature increase, ‘risks associated with tipping points become moderate’ and ‘increase disproportionately’ as temperature increases above 1.5°C (AR5). According to mitigation projections, global emissions would decline forthwith for a better than 66% chance of a 2ºC limit by 2100 (over 3°C after 2100). Failure to do so would risk the future sustainability of civilization and the human population. The IPCC does not make recommendations so this falls on scientists. By recommending immediate (emergency) massive action on CO2, the science community would make a momentous contribution to the future of humanity.

Global Security: Health, Science and Policy require about 10,000 words with footnotes

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/authorSubmission?show=instructions&journalCode=rgsh20

Style format APA

Papers of line all use links

Abstract (277)

Atmospheric Greenhouse Gas Global Public Health Insecurity Emergency

This paper argues that for global security, global climate (and ocean) change is an epic policy failure. As documented by the IPCC many aspects of human population security are already impacted adversely by global climate change. This paper features water, food, public health and economic security. Many regions have already experienced climate change driven disastrous impacts, and for global security the oceans matter. ‘In recent decades, changes in climate have caused impacts on natural and human systems on all continents and across the oceans’ (IPCC 2014 WG2 SPM A.1 p.4). Today’s global warming is already committed by the climate system to be much higher. Carbon feedback emissions will add further to the warming. Today climate change is a dire global security emergency for the future human population. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and atmospheric concentrations are increasing close to the worst-case scenario, with atmospheric CO2 accelerating at a rate without past precedent. National policy on emissions targets result in global emissions substantially higher than today by 2030. The overwhelming evidence (through 2017) is that today’s already committed global climate change is an extreme world security emergency, requiring immediate global emergency policies and actions as is recommended by climate scientists. The paper points that according to the science and the 1992 UN climate change connection policy making would be based on today’s atmospheric greenhouse concentrations and committed global warming, not today’s global warming alone. Key global emergency based policy recommendations, known for many years, are termination of fossil fuel subsidies (in short order) a carbon pollution charge (so-called tax), switching greenhouse polluting investments to making good money by non GHG polluting investments, and promoting the healthy climate friendly lifestyle.

Paper

First 1600 words

Introduction

The message of this paper on global security in this time of rapid global climate change is well explained in a 2016 paper by Yongyang Cai and Tim Lenton. To avoid catastrophic multiple interacting tipping points ‘the optimal policy involves an immediate, massive effort to control CO2 emissions, which are stopped by midcentury, leading to climate stabilization at <1.5C above pre-industrial levels. (Risk of multiple interacting tipping points should encourage rapid CO2 emission reduction, Yongyang Cai, 2016). www.nature.com/articles/nclimate2964.

One enormous group of tipping points is the vast amount of carbon that continued global surface warming will cause to be emitted, carbon feedback emissions released from warmed Earth surface. The obvious example is the increasing forest fires. The 2014 IPCC Assessment listed a number. Within this century, magnitudes and rates of climate change associated pose high risk of abrupt and irreversible regional-scale change in the composition, structure, and function of terrestrial ecosystems. Examples that could lead to substantial impact on climate (amplifying feedbacks) are the ‘boreal-tundra Arctic system’ and ‘the Amazon forest’. Carbon stored in ‘peatlands, permafrost, and forests ‘is susceptible to loss to the atmosphere as a result of climate change. ‘Increased tree mortality and associated forest dieback’ is projected to occur in many regions due to increased temperatures and drought that poses risks for carbon storage. (IPCC 2014 Assessment WG2 SPM p.16) http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg2/ar5_wgII_spm_en.pdf

The above paper reflects the overriding policy imperative from the 2014 IPCC Assessment, that global emissions of GHGs must be declining on an immediate basis (and can be) headed to near zero. The 2014 IPCC Assessment mitigation pathways ‘would require substantial emissions reductions over the next few decades and near zero emissions of carbon dioxide and other long-lived greenhouse gases’. (IPCC 2014 Synthesis SPM Headline Statements.) http://www.ipcc.ch/news_and_events/docs/ar5/ar5_syr_headlines_en.pdf

CO2, methane and nitrous oxide are the long lived GHGs in the atmosphere. Long-lived greenhouse gases (LLGHGs), for example, CO2, methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), are chemically stable and persist in the atmosphere over time scales of a decade to centuries or longer, so that their emission has a long-term influence on climate’. (IPCC 2007 Assessment) https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/wg1/ar4-wg1-ts.pdf

The national and international climate change policies do the opposite. The International Energy Agency (the world recognized source for energy and fuels) projects a 30% increase in fossil fuel energy related GHG emissions by 2030. ‘In this analysis, global emissions under the NDCs are one-third higher in 2030 than they are today, reaching almost 42 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent (GtCO2-eq)’.

International Energy Agency Energy Climate Environment 2016 Insights November 2016 p.19 http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/ECCE2016.pdf

NDCs here are Nationally Determined Contributions or national emissions targets. CO2 equivalent includes methane and nitrous oxide along with CO2.

Under national emissions targets (as of 2017) global emissions will still be increasing by 2030 and lead to a catastrophic global warming of 3.2°C by 2100. UNEP GAP Report November 2017) https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/22070/EGR_2017.pdf

Catastrophic climate change can be defined as abrupt, past tipping points or as irreversibly adverse as in the IPCC 2007 and 2014 Assessments.

‘Risk of catastrophic or abrupt change’ (IPCC 2007 2.2,.2,.4) http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg3/en/ch2s2-2-4.html

Under the IPCC 2014 section Potentially Abrupt or Irreversible Changes abrupt is further defined as ‘a large-scale change in the climate system that takes place over a few decades or less, persists (or is anticipated to persist) for at least a few decades and causes substantial disruptions in human and natural systems’ or as ‘tipping points beyond which abrupt or nonlinear transitions to a different state ensues’ and in the same section the 2014 assessment defines a climate changed state as irreversible ‘if the recovery time scale from this state due to natural processes is significantly longer than the time it takes for the system to reach this perturbed state. In that context, most aspects of the climate change resulting from CO2 emissions are irreversible’. (IPCC Assessment 2014 12.5.5.21) https://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/wg1/WG1AR5_Chapter12_FINAL.pdf

A prolonged climate change driven adverse loss of water, food or health security to a regional global population therefore would be considered catastrophic for policy making.

But the climate policy emissions gap of today’s national emissions targets is much higher than 3.2°C, because of future climate change commitment due to climate system inertia lags. As explained later, the full amount of global warming to come caused by today’s atmospheric GHGs always lags behind the global warming of the day. The 3.2°C by 2100 would increase a lot higher after 2100, making today’s national emissions targets policy more catastrophic. It would also be further increased because the global warming projected from our GHG emissions does not include the extra carbon emissions from the enormous planetary surface sources of carbon feedback emissions, already referred to under tipping points.

Simple facts are that as atmospheric GHG levels rise, ocean heat increases, the global surface temperature rises, as does the greater future committed degree of global warming. As surface warming increases so do all the impacts, and so do amplifying feedback emissions responding to global warming from many enormous planetary sources of extra emissions. There are no opposing feedbacks that could prevent this. Global warming will; inevitably cause more global surface warming in this way. At the same time as atmospheric CO2 increases so foes ocean acidification.

Of all the GHGs, according to the WMO, CO2 is contributing the most to global climate change (65% of the heat forcing), followed by methane (at 17%). https://public.wmo.int/en/resources/library/wmo-greenhouse-gas-bulletin

As well as the 2016 paper by Yongyang Cai and Tim Lenton, all sources in general project that an immediate decline (by 2020) in global emissions is required to limit warming to 1.5°C and 2°C, just by 2100. In the 2014 IPCC Assessment this is the best case scenario (RCP2.6) which is the only scenario not above 2°C by 2100 and requires global emissions declining by 2020. (IPCC 2014 Synthesis presentation p.20)

file:///C:/Users/Peter/Downloads/ar5wgiipresentation-141209082729-conversion-gate02.pdf

In the 2016 update of the INDCs (‘intended nationally determined contributions’ or national emission targets) the UN Climate Secretariat recorded a greater than 66% likelihood of staying below to degree 2°C by 2100 with ‘immediate onset mitigation scenarios’. However the same update projects that national policy targets will result in substantially larger global emissions by 2030 and still increasing.

(UN Climate Secretariat, 2 May 2016, Aggregate effect of the intended nationally determined contributions: an update Synthesis report by the secretariat, Figure 2, legend number 4, P1 scenarios)

https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2016/cop22/eng/02.pdf

Another expert paper saying the same is from James Hansen. ‘Rapid emissions reduction is required to restore Earth’s energy balance and avoid ocean heat uptake that would practically guarantee irreversible effects’. (James Hansen, Assessing “Dangerous Climate Change, 2013)

journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0081648

This paper features water, food, and public health security. With the worthy intention of mitigating disastrous on-going impacts to water, food and health security, the science and policy global warming target since the 2015 UN Paris Agreement is now 1.5°C, not 2.0°C any longer. Global warming targets by 2100 however are far from safety limits because warming will be committed to increase considerably after 2100.

Today the world is a global warming of 1.1°C for 2016 as recoded by the WMO 2017 State of the Global Climate in 2016 p.4.

https://library.wmo.int/opac/doc_num.php?explnum_id=3414

The paper mainly relies for impacts affecting security on the assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), with World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for current data. All global warming degrees are given compared to preindustrial. The smoothly projected future global average warming and impacts do not include sudden non-linear changes, tipping points or extreme weather events (like heat waves). The IPCC assessment has three Working Groups namely WG1 for the science, WG2 impacts and WG3 mitigation. The IPCC WG SPM reports (Summaries for Policy Makers) mean that the world IPCC scientists and all world governments have examined and approved these summaries for policy making. (A multistage crucible of revision and approval shapes IPCC policymaker summaries, Katharine J. Mach, 2016)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4975554/

The well known large distant future sea level rise issue is not included in this paper, only its present and short term impacts.